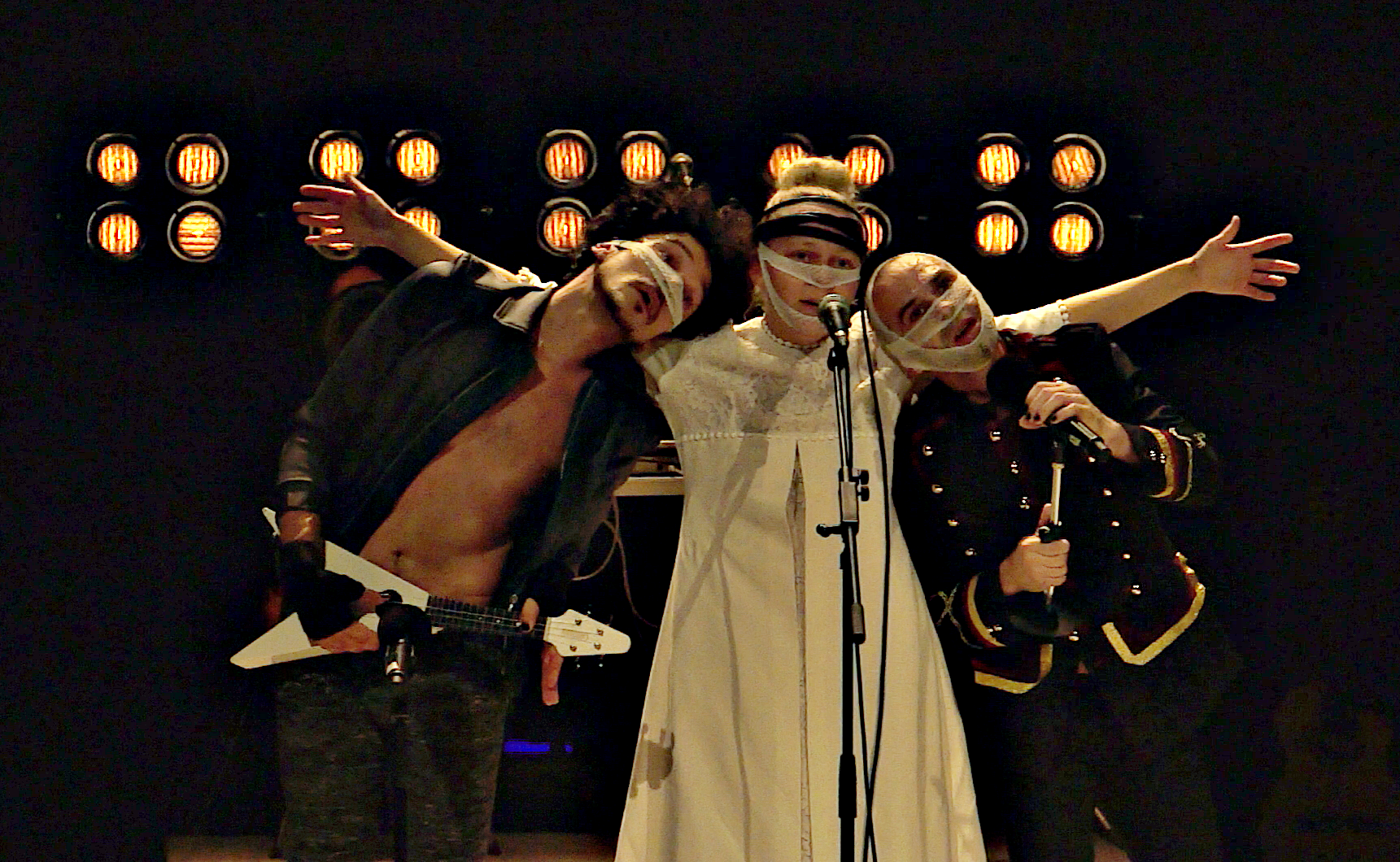

Come taste the wine, come hear the band ! The eclectic Catalan artist, poet and performer Kiku Mistu presents an innovative new project at Barcelona Festival Grec, from the 8th-12th July. Masks are whipped away and the audience is invited to participate in a transformative experience; an evocative, humorous and deeply compelling re-presentation of death – and on the flipside of the same coin – of life itself.

Art has the right (but not the obligation) to be used for social good, he claims, and this belief is the cornerstone of the Centre Cultural Imaginari which Kiku Mistu founded 20 years ago, in a small village in the province of Tarragona. Its leitmotif is “artistic interventions for a better or different world,” and its intention is to go beyond art for its own sake. The artistic content of “L’Ultim Cabaret,” (The Last Cabaret) is matched by spiritual and humanitarian aspects, and it stand out as one of the highlights of Barcelona’s international summer cultural festival.

What is “cabaret” for Kiku Mistu? A good question, he says. Like most art forms cabaret means something distinct for each person, based on their personal experience.

“I’m 50 now, and was lucky enough to be born in a city like Barcelona. Franco’s dictatorship ended in 1975, and there was a long transition of at least 10 years during which the cabarets absorbed all the more transgressive movements. In the 1970s, 80s and early 90s cabaret represented freedom. I’ve always had a curious nature and first discovered these cabarets as a teenager. They opened a portal into a world that fascinated me with its underground trends and unconventional actions such as men dressing as women.”

At its most profound, cabaret captures the tension between transgressive action and a primal urge for freedom that needs to be expressed. There’s also an element of nostalgia and pain inside the recognition that freedom needs something to grasp onto, which leads us reflect on who a “cabaretero”, or cabaret performer, really is.

“It’s someone who needs to hide their truth, that they’re an artist, they’re gay, they think differently to the rest of society… On the one hand the cabaretero represents the modernity and freedom of daring to demonstrate the unconventional, but it is also veiled by a sadness and frustration of not feeling that you’re really understood.”

Kiku Mistu decided to develop this symbol of the cabaret as a paradigm of the human condition. Deep down he feels that we all have a cabaretero inside us, a character than needs to put their make-up on and hide behind a mask in order to confront everyday reality. Below the mask there’s a sadness, like the artist who comes off stage and goes home after the performance, confronting their own solitude and vulnerability.

Cabaret is also representative of our human need for applause from the public, and the appreciation and approval of other people. We all hide behind a mask and need approval.

When Kiku Mistu decided to write about death, he wanted to take an ironic and humorous angle, to make it more approachable. The music and songs, burlesque and banter of cabaret provided a good structure.

Does he consider the cabaret as a personal metaphor for his life, or does he have other metaphors?

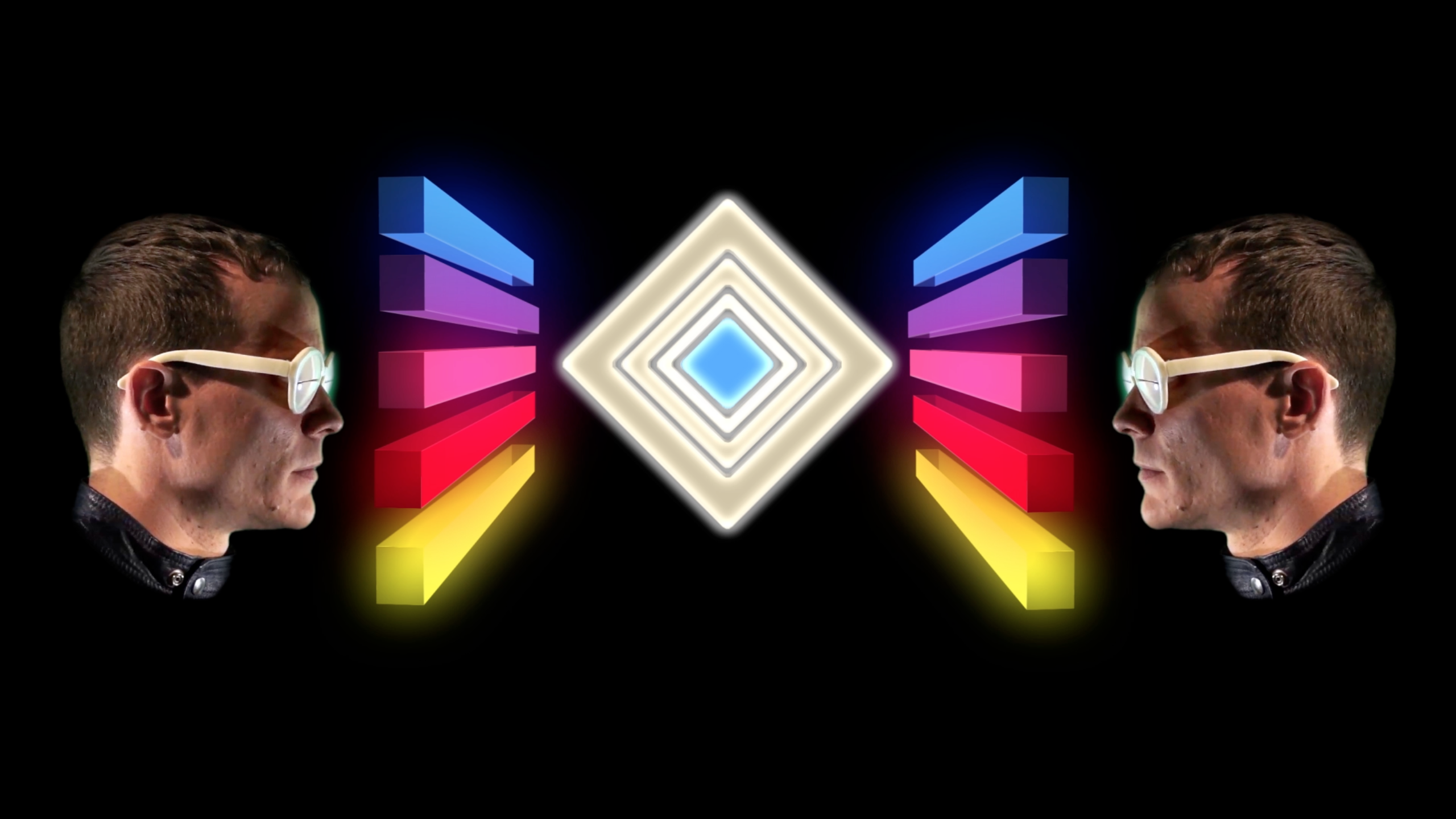

“I think that we all have multiple metaphors, because everyone has so many facets. I’ve got multiple personalities – we’re all a bit schizophrenic in our society. There are so many metaphors. We all potentially have a mother, a strong man, a serial killer, and a saint inside us. I think the objective of this life is to discover all these metaphors, and develop those that interest us most. People are shocked when someone commits a murder. It’s easy to wonder how a person can do something like that, but it depends on their circumstances. If we had different experiences and permitted certain facets to emerge then we might discover more hidden sides to us. I’ve realized that we are infinitely small, but also infinitely immense, and can fall into being any kind of person.”

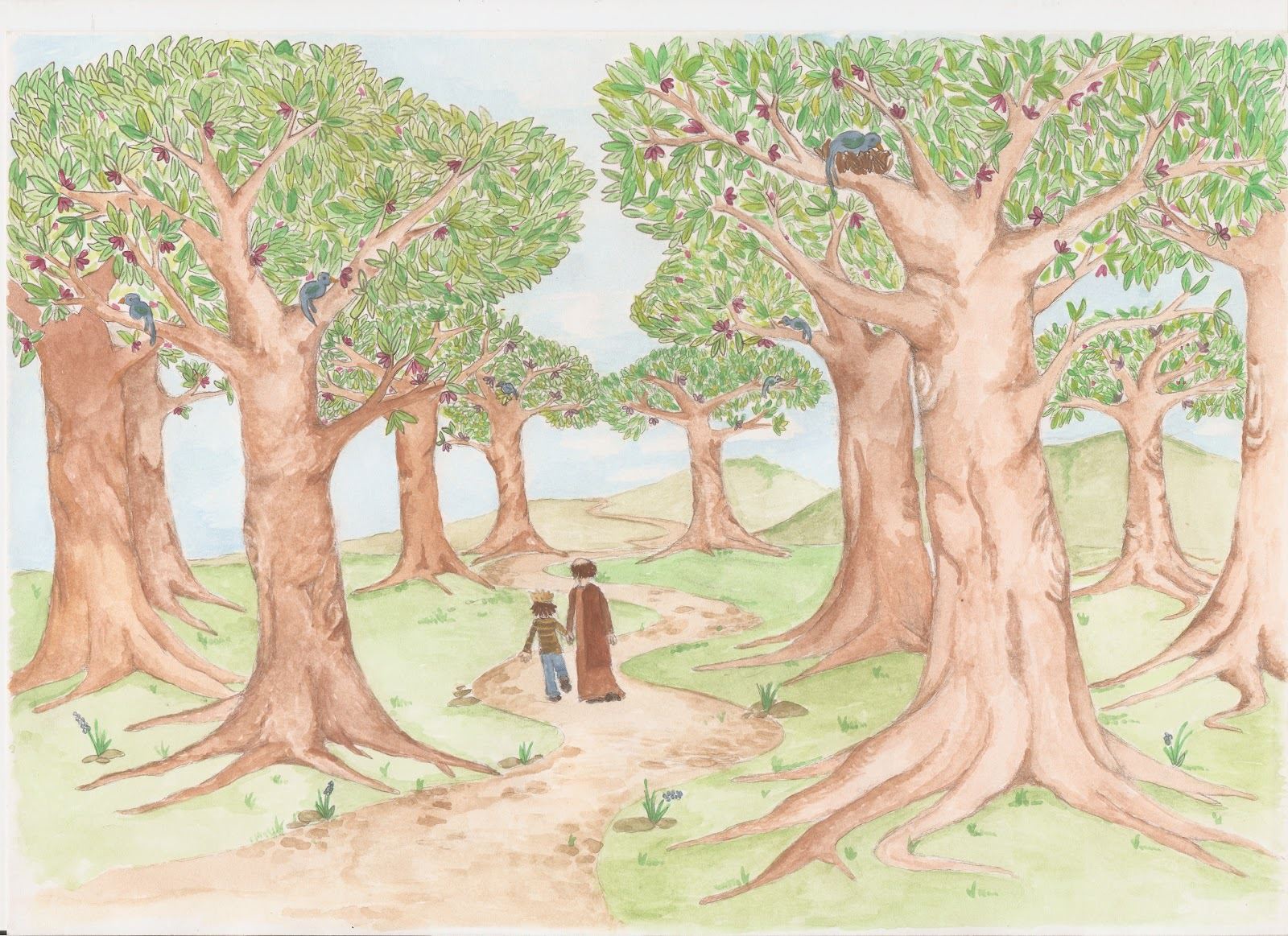

During the last 3 years he has worked with the metaphor of life as a journey that we are walking through. He shares that he lives in a small village of 10 inhabitants in the province of Tarragona, with his husband, chickens and donkey, and loves going for long walks in the countryside. “I was out walking one day and I realized that I was experiencing a very profound connection with nature, the universe, and myself. I felt it would be interesting to share this experience, not just the physical exercise but the mental, spiritual and artistic aspects.” This inspired the project “Homo Viator,” Latin for “the traveler”, in which 8 participants would walk with him and his donkey for 5km in the mountains.

He presented some works and characters along the way. Participants were very involved – digging in the ground to find things, and encountering powerful symbols such as a hanged man puppet in a tree. Poems were read and debates were opened. This intimate experience all revolved around the metaphor of walking through life, and life as a journey with things that affect us. We meet some people along the way who will stay with us forever, and others who we forget the same day. “That was the metaphor of the walker. Now I’m working with the metaphor of cabaret,” he adds.

Does he have any reflections on how our culture deals with the concept of death compare to other cultures?

“Of course. The Last Cabaret was specifically written for our society, which is so afraid of death and turns its back to it. But death is the only certainty in our lives. Other societies treat it in a more relaxed way,” he says, and goes on to add that one of the taboos about death that makes us consider it ugly is because in our culture its aesthetic is ugly. Cold marble, and cremation boxes. In other cultures it’s a colourful celebration of life. We have also lost the more primitive and instinctive aspects of letting our bodies react to emotional loss, from crying deeply to dancing uncontrollably.

Whilst reflecting on the death of several people close to him; his mother, two brothers, and several close friends, Kiku Mistu realized that he needed to confront his own death though a personal process. And as an artist, it seemed interesting to share this though his work. He chose the structure of cabaret to express this theme in a way that could reach as many people as possible. When you reconcile with something you can perhaps transcend it, and the best way to let go of our fears is by laughing. Laughter is one of the tools that can help us to understand and confront our own death, he suggests.

The Last Cabaret is centred around twelve coffins, each designed according to a different metaphor and with a different and familiar design. The public is invited to participate directly and step inside the coffins. “It’s very poetic,” he explains. “By taking it away from the intellectual and making it more experiential you’re breaking boundaries.”

One of the coffins is like a child’s cradle. Through this metaphor, which can be very strong for some people, reconciliation is possible. After all, countless initiation rituals and spiritual traditions whisper that we need to die to be reborn, to die before we die. Over and over again. Fall in order to pick yourself up again. Separate from someone in order to realize what deep love really is. Leave your home to appreciate that it is a part of you. These kinds of small deaths regenerate us, make us vaster and more intelligent. Kiku Mistu proposes that perhaps physical death isn´t any different. “We are all part of this large net of the universe, we shouldn´t be afraid to die because it’s all connected. I wanted to approach this reality, through metaphors that show that death is a part of life, always surrounding us, and to remind us that too often we’re devouring the great feast that is life without remembering to taste it,” he says.

There is a coffin with a bath tub full of rose petals. Another is vertical, like a clock. And another converts into a luxury table with two chairs that evokes our unconscious devouring of life. There’s also a double coffin, the marriage one, for 2 people. “When it was being built in the carpentry studio my husband and I climbed in. It was such a fantastic experience, I completely recommend it! It’s so profound; there are no words for it! To get into this double coffin with the person that you love is the most poetic and romantic things that there is!”

Is the theme of wearing and removing masks something Kiku Mistu has had to work on in order to express himself through his art, or has removing masks come naturally to him?

“I’m not sure if I´ve worked on it or not, but it has always been a recurring theme. I knew since I was a child that I never liked masks, and I’ve always tried to be very honest. It’s one of my main defects and problems. As an artist when you’re honest it can be difficult to compete in this world where costumes are valued so highly.”

Paradoxically, it’s by being so honest with himself that he was able to create the character of “Kiku Mistu”. Whenever he wanted to wear an old-fashioned tie or a skirt he felt that he was being authentic, honouring one of his multiple personalities which are as valid as the more formal ones.

“After all, why should we dress as society says we should? I personally like wearing long skirts, for example. And when you like something, then let yourself do it.” By giving yourself permission, you’re also giving other people permission to be themselves.

“I remember I never used to walk bare foot around the village because I didn’t want people to think that I was a hippie, or that I had some kind of Messiah complex. But so what if they think that? If you like doing it, do it. You’re not hurting anyone. Maybe there is an afterlife, or reincarnation, we don’t know. What we do know is that we need to make the most of this lifetime. So be yourself! Discover what this self is! The sooner you accept you’re going to die, the sooner you’ll appreciate that you need to live and savour the life in front of you, moment by moment. We are all protagonists in our own adventure, in our own novel,” he enthusiastically urges.

The conversation turns to one his ongoing projects, the “Tapas Parapoeticas,” poetry and performance evenings. How does he select which poems to read?

“It’s easy for me as I’m not an intellectual. I don’t know as much poetry and literature as I’d like to. I’d love to have the time to read more. I’m very sincere and simply choose whatever has made me vibrate, whatever I like. I read some of my own poems, texts that come from the heart. I’m not a writer but I consider myself a poet of life. At the end of the Tapas Parapoeticas people often tell me that they hadn’t realized they liked poetry, and that makes me immensely happy.”

This brings to mind a statement by the literary theorist Jacques Lacan, who once said “I am not a poet, I am poem being written.” How does Kiku Mistu identify with this?

“With all modesty, I identify completely. Not just about myself though, I think that all people are a poem being written, and that’s why it’s so important for us to be ourselves. The fact that poetry isn’t considered fashionable indicates that things aren’t going well in our society. I’ll invent a word now –our “sociopoetic” index is low. We should be surrounded by poetry! If we were conscious that we are all potential poetry, then we’d try to be more in tune with ourselves and be more conscious of what we’re consuming, and pay more attention. We’re like instruments that are out of tune. I am grateful for the good fortune of dedicating myself to art. I consider that I am poetry in motion, and so are my dog, my donkey, and all the countryside. This is why I feel the obligation to make my house as elegant as possible, as poetic, sweet, pleasant… also my clothes, my words. If we all tried to make our lives more poetic, the whole world would be extraordinarily beautiful. If everyone looked after themselves and the square metre around them, so many of the world’s problems would be resolved immediately. Our society’s values are all upside down. Right now, to be revolutionary, you need to be a poet.”

What does poetry mean to him?

“It’s complicated… when I give classes or workshops I like to ask the same question, and all the students get blocked. Everyone knows, but it’s hard to explain. Poetry explains the inexplicable. This is why it’s so hard to explain. It is many things, from a smile to a tear, to a flower in this precise windowsill with that exact ray of light touching the petals.”

Perhaps some of this difficulty lies within the question itself. “What is…” is the language of logic. Poetry is in another realm, so we can’t explain it from here. Instead, it comes from our deepest depths, from the most internal part of us, which we often struggle to find.

Poetry is reaching closer to the unknown, to that which can never be known. “You can’t describe the touch of a loved one, a sunset, or what you feel when you’ve heard that a plane has crashed and everyone has died. You discover how impotent we are, and yet how immense we are too. You discover you have all these huge feelings. Every one of us is so unique, and we are poetry that is being written,” he adds.

“It’s important to remember that you need courage to be yourself. It’s a basic requirement for authenticity. You need to be brave to remove your masks and to face the world as you really are. And this is how we can increase the sociopoetic index.”

We pause a moment, and start to discuss other ways in which the sociopoetic index can be raised. Firstly you need to acknowledge and discover the poetic potential inside yourself, which for many people is a long and arduous journey in itself. After all, if the government wanted people to discover their poetic potential, there wouldn’t be a 21% VAT tax on cultural activities like theatre tickets. We would make more choices based on poetic criteria, or they at least would consider them more carefully. For example, aluminum window frames have certain advantages, but they are less poetic than wooden frames. If you have a flower in your terrace, and you water it and talk to it every day, your life will be more poetic. It’s about being tenacious, discovering the values of poetry, and especially, being courageous.

“Be aware that the prize you gain is immense – being yourself and being surrounded by poetry is amazing,” reflects Kiku Mistu. “It may come at a high price, but it’s worth it. I’ve achieved my poetic dreams, but I’m not rich in a society that values money. Yet I’m immensely rich in a society that values art, and am lucky enough to have discovered a long time ago that I am a poem being written, and that I am the only person who can write it.”

Ladies and gentlemen, welcome to the Cabaret.

L’Ultim Cabaret (The Last Cabaret) will be showing at the Espacio Patti Manning, Barcelona, from the 8th-12th July.

Kiku Mistu Centro Cultural Imaginari