Art can lead us deep into our nature, and Chitrangada has curled softly into her dancers who present a powerful poetic experience through this dance drama. With all four nights at Sala Hiroshima (28-31 Jan) already sold out, and plans for a national and international tour in the pipeline, performance producer and lead dancer Shreyashee Nag’s eyes shine as she speaks.

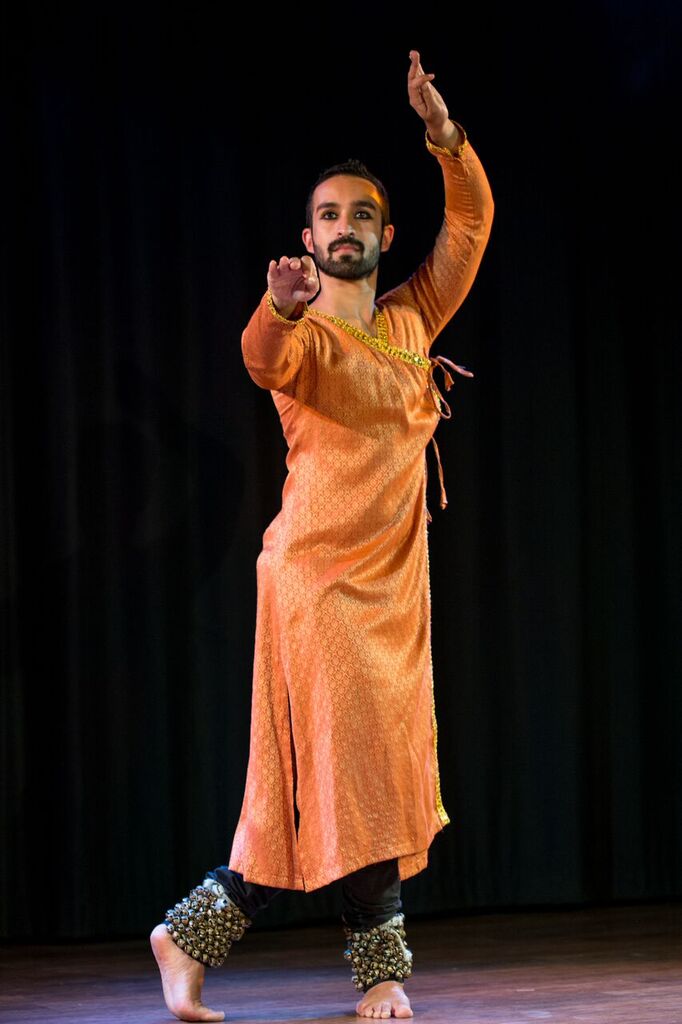

Originally from Calcutta, Shreya has been living in Spain for 14 years and in Barcelona for the last four. A profound love for her native Bengali culture has always stirred in her heart and gave birth in 2013 to Núpura, an association for sharing Southern Asian culture and especially for creating kathak dancers in Spain. Most classical Indian dances are from the East or South, and kathak is the only classical dance of Northern India. “Kathak” means to tell a story, and this is the dance art of storytelling, from Hindu mythology to kings and queens and our own lives, through a lineage and legacy to which Shreya’s company faithfully belongs.

Núpura’s art director, Fasih Ur Rehman has more than 30 years’ experience and is considered the most important kathak dancer in Pakistan. Other mentors include Sujata Banerjee, director of the Asian Department of the Imperial School of dance in London, and visiting teacher Prashant Shah.

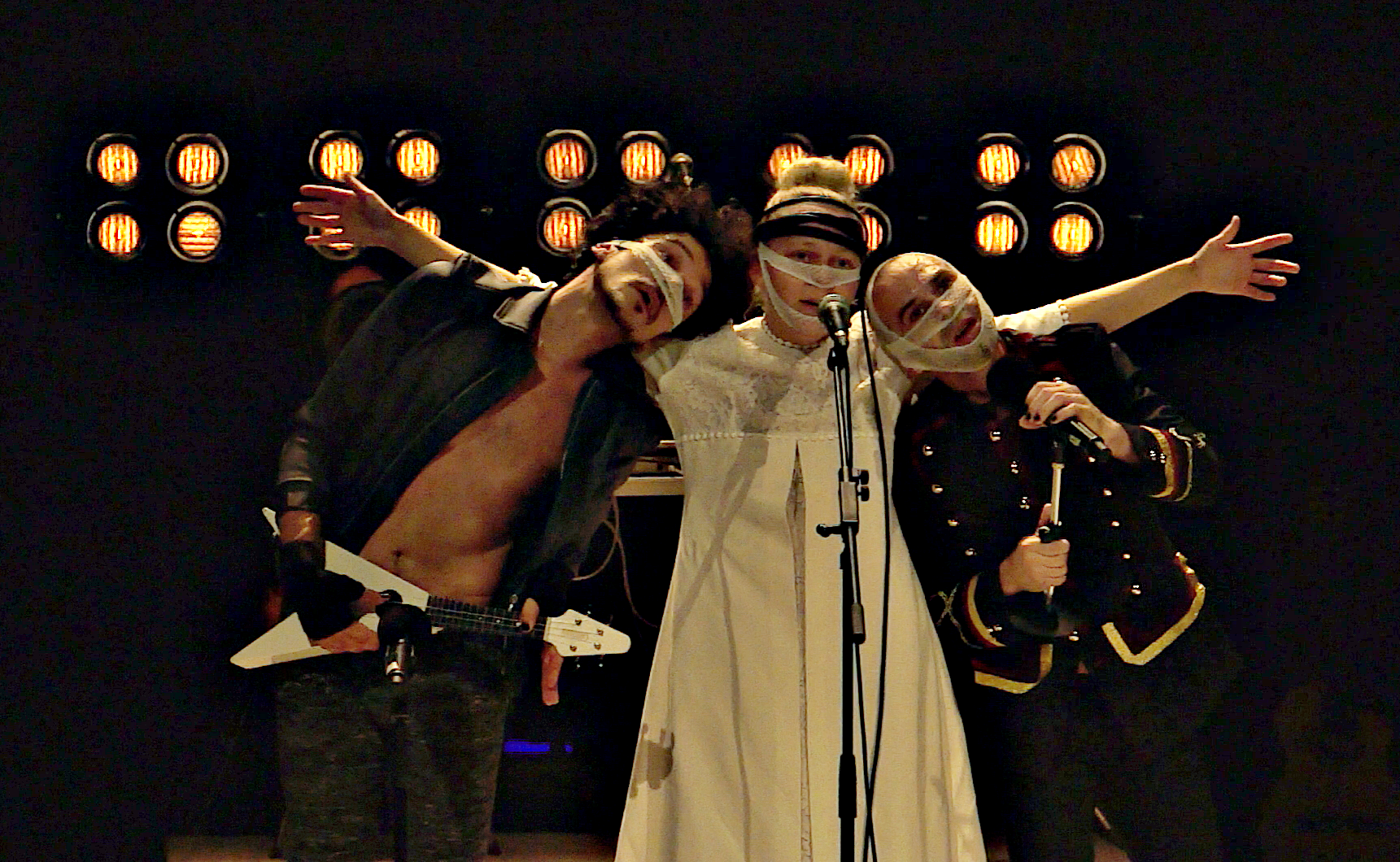

This new performance of Sóc Txitrangada is a Catalan translation of the dance drama Chitrangada, based on the play Chitra by the great Bengali poet and artist Rabindrath Tagore. Inspired by the love story of Chitra and Arjuna in the classical Indian epic the Mahabharata, Tagore’s text from 1936 was originally used in the fight for women’s equality. As a timeless work of art it still continues to reflect contemporary struggles which now speak of gender and its many levels of discrimination.

“Even though we have a male or female body, many people don’t want to be defined this way,” explains Shreya. “I think it’s important to understand that we all have masculine and feminine energy inside us. Some have more of one or the other, but this duality is universal and it’s something we need to embrace and grow. We must be open to discovering this, and not afraid of it.”

We touch on a key theme. Fear is perhaps our primary block, especially fear of not being accepted for who you are. As a warrior princess defending her kingdom, all was well until Chitrangada fell in love with the renowned hero Arjuna. Pained by his indifference in their encounter, she turns to Mádan, the God of Love, and begs him to make her spectacularly beautiful so she can win the love of her life. Her strong body and manly appearance blossoms into feminine beauty and grace and Arjuna falls for her. However, she now carries a new pain of not being who she truly is.

Arjuna hears of this ambiguous warrior princess and is fascinated. The villagers tell him that regarding the love of a woman she is a woman, but a man when fighting wars. In fact, she’s the perfect combination of man and woman: someone beyond gender. After all, the poetic drama challenges, does it really matter? Arjuna’s interest sparks Chitrangada’s awareness of her intriguing personality and reawakens her sense of authentic self and its value. Her inner cry of “This is not me!” becomes louder as she realizes that she can sacrifice her love, but not who she really is.

And this is where the magic of kathak dance takes the narrative to another level.

“When you’re telling a story of Raha, a very feminine goddess, you become her. And when you become Shiva, the destroyer, you must connect with the masculine energy inside you to become him. It’s not about faking an attitude. Without sincerely feeling both your masculinity and femininity it wouldn’t be possible to perform a sincere dance.” For the dancers, explains Shreya, Sóc Chitrangada has been a long process of connecting with both aspects of this duality, feeling it, and expressing it artistically through movement.

Before meeting Chitrangada, Arjuna had taken a vow of celibacy. His love for her beauty dissolves this mental identity construct, aligning him more with his true nature as a man. For Chitrangada, however, love made her reach towards ideals of femininity and an identity she thought she should have in order to be desirable, and away from her nature. Tagore’s subtle insights touch on an experience shared by many women; losing their true centre through insecurity and a desire to please (which is fully exploited by the fashion and cosmetics industry). Chitrangada’s empowerment begins when she realizes that she doesn’t need the external beauty of Mádan’s magic. She can feel the womanliness inside her whenever she wants.

“This is why I gave our performance the slogan –ets el que desitges ser – you are what you want to be. You don’t have to do anything to be what you are,” says Shreya.

She gives a real life example of a person born in a man’s body, who wanted to become a woman for his lover. There was no God of Love, there was a surgeon. He started going through the transformation and was delighted with his new breasts. But by the time the day came to have the more complex genital operation he had deeply questioned himself and decided not to go ahead. He wanted to be himself and to be loved by his man as he was. He returned to his previous form, but continued to say he was a woman inside.

“Why is being a woman about having a pair of breasts?” asks Shreya. “It’s about feeling it. I feel like a woman, I don’t need to prove it by having breasts.” It’s an example that immediately draws our attention to the difference between gender, which she is clearly referring to, and the physical attributes of a woman.

Our conversation turns back to the slogan -you are what you want to be. We tend to have many barriers: social roles, personal blocks and limiting beliefs that sabotage our innate creativity and its authentic expression in each present moment. What clues does this performance give about how to align with the actions and thoughts that create a reality of being what we want to be?

“We need to really open our minds, and especially to understand that we are constantly over-defining ourselves, and yet we’re evolving constantly. For example, men have feminine emotions too. But if you close yourself by saying ‘I am a man, and a man is like this,’ you don’t allow yourself the space to enjoy them. You need to take a step beyond playing roles and break this defining disease we have. ‘She’s a real woman.’ What the hell does that mean?! These phrases are so common in our society. I want people to close their eyes and open their minds, and just feel the masculine and feminine inside, and explore these aspects of themselves.”

How does it feel to dance Tagore’s poem? Knowing the Bengali language helps, Shreya admits, as it’s easier to relate to the words and cultural context.

“Bengali is very circular and sweet, with a lot of ‘o’ sounds. The beauty of dancing a poem comes from understanding the essence behind the words, feeling it in your mind and conveying the emotions through the body.”

The text is being performed in Catalan for the first time, with translation supervised by Agustín Paniker. Did taking an ancient Indian story and presenting in a different language, though a different culture, bring up any difficulties or challenges?

“The only doubt I had is that Bengali is a beautiful soft language, phonetically speaking. My only question was what would it be like to listen to the poetry of Tagore, which is so beautiful, in Catalan or any other language? I had nights when I couldn’t sleep, wondering how to do justice to Tagore’s words and emotions through Catalan.” Working on the emotional expression of the dance got her through those dark nights. “Catalan is the structure through which the emotion is conveyed, so the emotions have to really shine out of each dancer.”

Shreya is a believer in thinking local and acting global. “Chitrangada can’t stay in Barcelona, she has to fly!” They are planning to take this performance to Madrid, Bilbao and outside Spain. London is on the list. So is India.

“I definitely want to take it back to its roots, with Spanish people performing Tagore. It’s one of my dreams. I won’t be Chitrangada in India, there’s nothing special about a Bengali performing in Bengal. There’s nothing like showing the people in India what we’re doing outside India.”

If you weren’t quick enough to get a ticket for the upcoming performance there will be more opportunities to share Núpura’s kathak storytelling journey as it continues to unfold through new projects in Barcelona.

Our nature leads us deep into art.

Sóc Chitrangada?

Somos Chitrangada.

Sóc Txitrangada: 28-31 January 2016 at Sala Hiroshima- C/ Vila I Vilà 67

www.hiroshima.cat

Sóc Txitrangada is part of the Otra Danza program at Sala Hiroshima, which presents new artistic interpretations of traditional dance. These include a new perspective on butoh by Yuko Kawamoto and original flamenco fusion shows.

[…]

[…]